I still feel a twinge when I think of my high school best friend, Sharon (not her real name). After graduation life pulled us in different directions, and we lost track of each other. But we managed to find each other several years later, and we had a visit I’ll never forget.

Sharon told me about her successful professional life and her marriage, which she claimed was a happy one. But later in the conversation she confided that her husband Jack was extremely insecure and jealous, and had told her he would leave her if she related freely to other people. Afraid to hurt him and risk losing him, she was doing her best to comply with his ultimatum, but it was painfully obvious to me that her obedience was taking a huge bite out of her emotional well-being and actually driving her crazy.

The Sharon I knew and loved in high school was an earthy, passionate, vibrant young woman, who savored life to the max. She was naturally warm and outgoing. Now married, she was valiantly trying to suppress her impulses and control her behavior, but she couldn’t change who she was and what she needed. She confessed to me that in spite of her efforts she was finding herself craving social contact even more, and had even begun to secretly give in to her desires. Of course she felt terrible about it.

Her marriage was obviously hurting her, yet she was unwilling to admit that. She and Jack were very attached to each other, so she clung to the belief that her marriage was excellent; it was she herself that was flawed. As a result, her self-esteem was in the toilet. She needed help, but she couldn’t talk about her feelings to her husband. And she wasn’t allowed to talk to anyone else.

Sharon’s story is an extreme case of unhealthy attachment, but it points out a common danger. Sharon and Jack made an agreement that many couples make: “Be my one-and-only, and I will be yours. I will love you and only you.” Couples don’t always reinforce the pact with explicit threats like Jack did, but an unspoken threat hangs in the air. What would happen if either of them strays across the line they’ve drawn? And if it’s discovered, will the relationship survive? Oftentimes, it doesn’t.

Individuals who maintain significant friendships with the opposite sex do run some risk of falling in love, or at least falling in lust. One cannot deny that considerable maturity is required to maintain faithfulness while enjoying social contact with members of the opposite sex. Realistically, the necessary maturity isn’t always there.

Thus, most people believe that the safest way to ensure faithfulness over time is to keep temptation to a minimum, by minimizing significant interactions between the sexes. Often however, the allowable involvements are reduced to a degree which can be unhealthy both to the relationship and the individuals in it.

We all want our love to last forever. And it is perfectly reasonable to want to maximize the chances. But people go too far when they agree to not only avoid and prohibit sexual infidelity, but also anything they assume might lead to temptation, like socializing or making friends with someone of the opposite sex. Sometimes they even go so far as to discourage same-sex friendships.

Couples feel the need to restrict each other, because they intuitively understand that it is natural for all human beings to love more than one person. It’s part of our inherently social makeup. But instead of accepting that as a natural expression of who we are and an actual psychological and emotional need, when we’re attached to someone we view it as a threat. We assume that “one thing WILL lead to another,” that none of us can be trusted to keep our desires in our pants. So we create rules and agreements, and threats to enforce them. And we assume they will work.

According to the popular ideal of romantic relationship we are supposed to be completely sufficient as a couple. We buy the lie that human beings CAN be happy loving only one, that one person CAN fill all the needs of another. We tell ourselves, and promise each other, that we will be completely fulfilled by our relationship. And we worry that if we’re not the one-and-only for our lover there may be someone else who is.

The inconvenient truth is, no one person can possibly be all any other person will ever need. Human beings just aren’t built that way. Without freedom and the continued enjoyment of a larger sphere of relations in life, people are not truly happy. Even those who surrender quite willingly—even enthusiastically—-to an exclusive commitment tend to want breathing room eventually. A relationship that excludes all others is much too cramped and small for the human spirit.

To be whole and healthy human beings, each of us needs a variety of relationships. We all have more love and caring to offer than any single person can accept. To feel fulfilled as the givers we inherently are, we need more than one person in our world to love, care about, and contribute to. Each person in our lives brings something different out of each of us, and allows us to discover and be more of who we really are.

We also need people in our lives who inspire us; who show us different approaches and solutions than we tend to think of on our own; who can understand our specific challenges because of shared interests or common experience. We need companionship and camaraderie. We need friends to laugh with and cry with. And it helps a lot to have a friend’s perspective on our struggles and progress.

So when couples lay down the law to limit each other’s social outreach, they are breaking a bigger and more immutable law: the law of human nature. In so doing, their unknowingly undermine the viability of their relationship—even if neither of them ever “cheats.”

My visit with Sharon impressed on me the many hidden dangers of suppressing one’s partner:

We risk inflaming suppressed desires into full-blown obsessions. When someone can’t do what they want, and can’t even process the desire with someone else, they may find it hard not to keep thinking about it, which only strengthens the desire.

We damage our partner’s self-esteem. Our restrictions tell them that their natural impulses are bad and wrong—and by implication, THEY themselves are bad and wrong.

We cut off open communication in the relationship. If our partner has “illegal” thoughts and feelings, they won’t feel free to confess them to us or explore them with us. They’ve got to keep them bottled up inside, or turn to others for intimacy and advice. Over time, there will be more and more we don’t feel comfortable talking about together. We’ll gradually lose the intimacy and honesty of our most important relationship—with each other.

We stunt our partner’s growth when we prohibit broader social experience and social experimentation. Good parents recognize this. They understand that kids have a lot to learn; they need to try things for themselves and make their own mistakes. So they don’t tell their kids, “If you do this, I’ll hate you and never speak to you again.” They know the child would likely do it anyway, and simply stop talking openly to the parents.

How much better for the parents to let the kids do things, advise them how to stay safe, and invite them to talk it over afterward: “How did it work? Did it make you happy? What was good about it? What was bad?” That way they can be part of the learning process. They can help their kids review and evaluate their experience. Best of all, they can preserve the trust and openness in the relationship.

Adults aren’t so different from kids in this way. We still have a lot to learn. We aren’t finished making mistakes. And we still need someone to help us sort through and digest our experiences.

It’s not easy to be a “good parent” to a romantic partner. The idea of doing without restrictions is met with panic in most hearts. So is the possibility of having to talk about hard and uncomfortable subjects. The truth is, love requires emotional courage and self-transcendence.

When we take on a relationship, we take on a huge responsibility for another person’s spiritual and emotional well-being. People often don’t hold that responsibility seriously enough. They’re a lot more concerned about being able to completely possess this person than they are about the implications of the restrictions they impose. They’re not asking, “What is it going to do to my beloved to not to be able to do this?” They’re worrying about what they might lose if they allow the beloved to do it.

It all seems natural enough. “Doesn’t everyone feel this way?” we may ask. Perhaps the opportunity to feel that way is always there—just as the opportunity to flirt in the absence of restrictions—but if we take advantage of either opportunity, we risk hurting someone we love.

For our relationships to be strong, healthy, and lasting, we need to focus more on loving, nurturing, and supporting each other than on preventing each other from loving others. We need to extend trust in order to inspire and encourage trustworthiness in each other. We need to learn to exercise the patience, understanding, trust, and courage that keeps love alive and growing, instead of dodging those challenges and simply building walls to keep us together at all costs. It’s more challenging to meet the higher requirements of intimate relationships, but that’s by far the best way to create truly durable and resilient bonds of love.

Let’s call a spade a spade: To restrict and threaten isn’t love; it’s blackmail. It isn’t surrender to serving the well-being and best interests of the beloved; it’s surrender to paranoia and self-interest. It isn’t accepting the one we love as who they are; it’s insisting that they behave a certain way—or else.

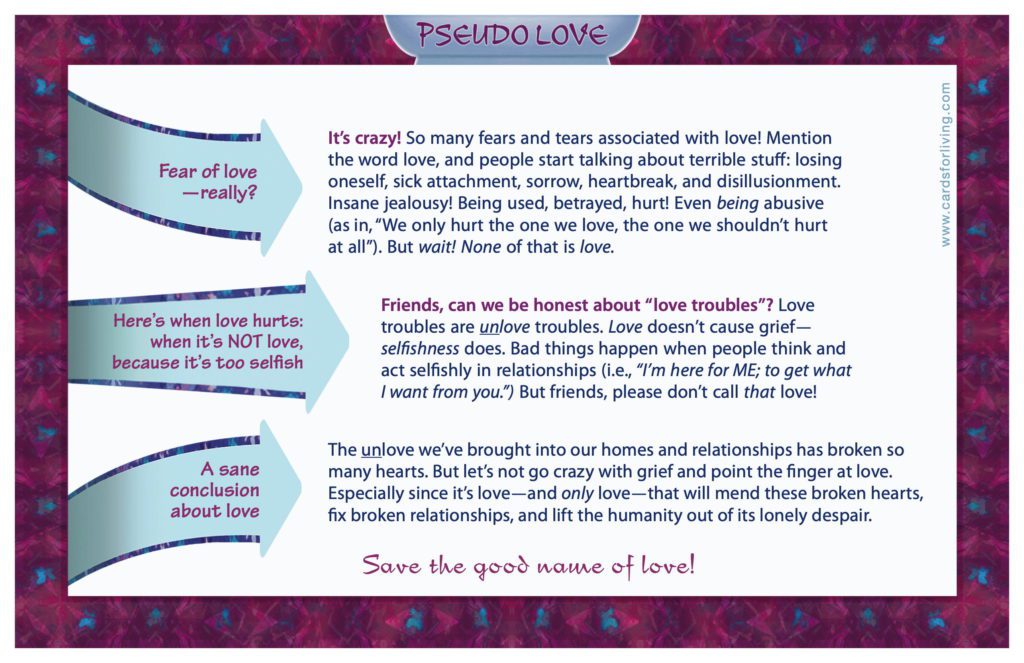

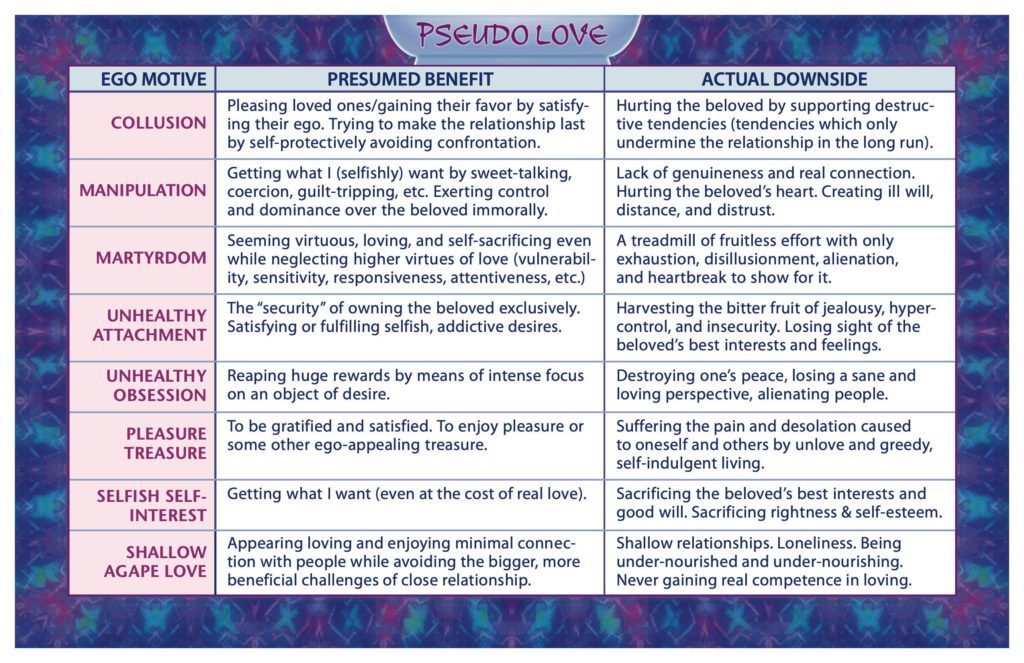

Possessiveness is just one way that unlove masquerades as love. To learn more about the difference between love and unlove and other common examples, download or print the Pseudo Love Card from the Cards for Living website.

Love,

Your friends at LoveTrust